|

Disclaimer: This unedited, rough draft material is a year-long project in response to our 2004 theme: pilgrimage. It is meant to be a dialogue between myself and my fellow Mammoths and any of you who happen along. It is intentionally not polished, nor is it finished. Charlie Buchman Ellis -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 weeks out from The Dwelling. We left the Dwelling in the midst of a snow storm, a heavy one; today the sun shone, the snow had holes and lattices of melted, then frozen water. And wind. Wind up to 47 mph. Gusts strong enough to topple trucks, bend trees, and make Kate, Frank, and Tom lean as we all hiked back to the white pine grove at Boot Lake Scientific and Natural Area. We stood behind the Tundra, Roxann, too, and Frank smudged us with sage and his eagle feather. Wind blew the sage smoke and our purification up, up, up toward the brilliant blue sky. Beowulf, conqueror of Grendel, his victim, too, burned on a funeral pyre, and, the poem recounts, “Heaven swallowed the smoke.” Let it be so still. This equinox day the four of us, Roxann stayed behind to avoid aggravating a broken ankle, visited a crooked, old pine. In the grove this pine has created, its children grow in great circles around it. A swamp on one side and Boot Lake on the other create a small sacred highway of land, no doubt held together, at least in part, by the root structure of the crooked pine and its children. Thus, the high ground represents the surface expression of cthonic work, work carried out over decades at least, perhaps even a century or so; and with enough result four of us could stand, quiet, alone with the wind, the tree, and the remains: feathers, bits of digested rabbit, pine branches, crowns of paper birch bark, the leavings of deer and rabbits, dry red needles, sticks and stones. The hike goes through a meadow formerly a homestead, then a birch and oak stand, low and later muddy, and often, in less snowy times opens onto a circular meadow. Today, though, the snow was still knee deep, so we skirted the meadow and went along a bit of higher ground above the swamp. Kate picked up a walking stick, first of downed birch, then one of oak. Tom and Frank sat on the forest floor. We were there, with the grove, the family of trees, between the waters, and, this day, always the wind. Branches whipped back forth, a roaring sound hovered outside. The dropping temperatures, already below freezing, made the time less comfortable, but no less memorable. We are animals. No matter what else we may be. And this earth is our home. No matter what other homes we may have, in the heavens or in other worlds than this. The wind, the melting snow, the sun higher in the sky and headed north, all these, too, are part of our home. They are the climate in which we live; the weather we face each day; yet, in so many ways, we pretend we have left home and need never return. This is not true. It is not true not now, has not ever been true, and will not, for the foreseeable future, ever be true. We need to feel the cold breath of home, hold the frozen water fallen from the sky, spend time with our brothers and sisters the plants and animals. We need them; they do not need us. Again, we pretend often this is not true, but it is. The evidence, however, was all on our walk this equinox evening. The deer leavings, the digested tufts of rabbit, the snow, the old and new trees—all these things there without human intervention, without human intention. All these things. The wind. The blowing wind. Before we got started Frank, and Kate and I sat in our truck. We watched a bird with a great wing span as it rode the thermals, spiraling higher and higher, wings hardly moving. Perhaps a spotted eagle, as the Lakota say; or golden eagle, as I was taught. Feathers. We found feathers, perhaps wild turkey, perhaps hawks. Feathers and wind. We do not need to compare the wind to the spirit, it bloweth where it will without the comparison. In its movement, invisible, yet powerful enough to bend trees, lift a great bird of prey high into the sky. Perhaps the allegory should traverse the opposite terrain, perhaps it is the wind that is like the spirit, rather than the spirit like the wind. That is, perhaps it is the wind, this angel(messenger) of seasons change that came first, is primary; who knows, perhaps the wind is spirit. Afterward, Kate and I attended a birthday party for our neighbor, Pam Perlich. Pam’s fifty today. In their house many, many people smoked. It was like a return to the 1950’s, a cocktail party. A strange end to the day.

Southeast Asia

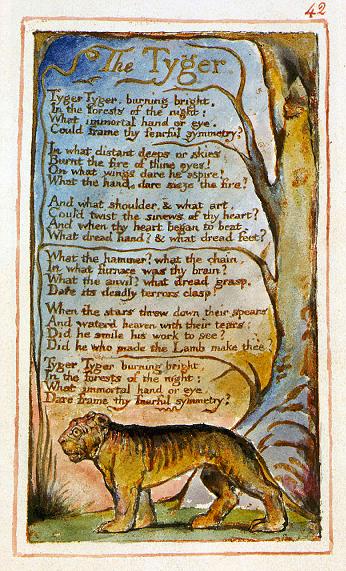

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

MANDALAY

My sister and brother have given the productive adult years of their lives to Southeast Asia. I wonder why. Did they want as much distance as possible between them and the family home? I know I did, but I didn’t happen onto foreign soil as the solution. At the retreat someone asked me if I saw the trip to Southeast Asia as a pilgrimage. I said no. The answer is true in this respect—I do not see Southeast Asia as a pilgrimage destination; it is not, for me, Mecca and my trip is not a Hajj. Neither is it Lourdes or the Louvre or the Uffizi or Delphi, Delos, Knossos, or Ephesus. The answer is false, though, in an important sense. Ancestor worship still dominates much of Southeast Asian popular religiosity. Mark knows a family who has their grandfather’s ashes on a family altar; Mary told me of the cremation of a friend’s husband, everyone got an invitation to the crematory to view the end. Gifts for the afterlife like hell notes, small houses, cars (all paper), other practical necessities burn at curbside Taoist furnaces. This trip is on my father’s nickel. His death put the cash in my pocket and I’m using it to visit the last of my nuclear family. They all (both) live 12,000 miles from home and it is time I went to see them. As the big brother, I have a responsibility to both of them, a filial duty I know is much like the family duty of Asian cultures. So, this is a trip, oddly, back home, a return to my roots though those roots have taken to earth far from the corn and soybean farms of central Indiana. This is a pilgrimage. I take it with a humility forced on me by the generosity of a man with whom I quarreled more or less constantly for the last thirty-five years. I take it with a purpose that would not exist without him and Mom. I take it, also, with a growing gratitude for the inheritance both Dad and Mom offered me, genetically and psychically. I could feel guilt or shame about coming to this gratitude after their deaths, but I don’t. We all did the best we could under trying circumstances. Now, in the liberation following their death, I can use the freedom gained to acknowledge them or to continue hammering away at them. I choose to acknowledge them, and to acknowledge their love for me and mine for them. So, thanks, Mom and Dad. This is a pilgrimage. I have never taken a trip to a foreign land without a profound experience of the other, and, of the other within me. I have no idea how I will connect with the other in Southeast Asia, but I know it will happen and it will change me at the core. How? I don’t, can’t know. This is a pilgrimage. I have three new books, one a loaner from Tom to share with you all, and two others, which focus on making travel sacred. A theme I’ve already discovered is the way medieval pilgrimages shaped our modern idea of tourism. Another theme I’ve discovered is the hiddenness of the pilgrim among tourists, pilgrim absconditis. I now see this trip as a pilgrimage in three ways: as a journey of family healing, as an honoring of my ancestors, and, as a journey to the home of the other, to the home of the other within. I’ll keep you posted on my preparations, as I get ready for a pilgrimage at the end of this pilgrim year.

Preparations for the Journey I have an odd way of preparing for a trip, half scholar, half pilgrim to the unknown. As I write I realize this is not different from the way I live my life. Hmmm... Anyhow, it goes like this. I search the web, holdings of libraries, bookstore travel and history shelves. I talk to folks I know who’ve gone this way before. My intent is to gain a lay of the land, a sense of the significant, both to me (as an outsider) and to the people who live and have lived where I’m headed. In this way I begin to piece together a broad itinerary—major destinations, rough times in each, a few sites not to be missed. Then I hit the phones and the web again trying to determine costs, see if my itinerary has financial feasibility. If it does, I take some care to learn about its chronological feasibility. Can I get to and from places in the amount of time I have available, or can afford? When I visited Dr. Gerst yesterday for my travel consult, he wanted to know where I was going, how long I would stay, what I’d be doing. Fair questions. OK. Right now: Singapore, Bangkok, Angkor Wat, Phomn Penh, and central Vietnam, possibly Burma: Mandalay and Pagan. How long? Hmm. Singapore 4/5 days, Bangkok 3 to 4 days. Angkor Wat 2 days. Phnonm Pehn 2 days. Vietnam. 3 or 4 days. Maybe onto Mandalay where the flying fishes play. Say 4 or 5 days. Then, back to Singapore. Or, something like that. Will you go to the Myanmar/Thai border in the north? Don’t know. Because there’s a different form of malaria there. Will you spend time in Thailand outside of Bangkok? Don’t know. Maybe. Well, for me to protect you I need a better sense of where you’re going and how long you’ll be there. The other half kicks in here. I need—not want—flexibility. I want to follow the lead I got from the guy at the noodle stand about an interesting place to visit. Maybe, like when I was in Mississippi a couple of years ago, there’s a local festival happening that’s not in the books, maybe one that happens only occasionally. I will want to go. And matters are always different on the ground. What seems significant to me in Andover, Minnesota, aka heart of the North American continent, may look very different in the steamy tropics 12,000 miles from the seven oaks out my study window. My interests in art and religion, cultural uniqueness, food, and natural sites make me a sucker for the off-beat, the odd, the unusual. It often doesn’t show up in guidebooks. I may have mentioned a few weeks back the iris blooming in the bayous in April, just as the alligators awoke from their winter sleep in the mud. I found these because New Orleans and the French Quarter, on other visits a real fascination for me, felt stale, cliched. So, I decided to see a bayou, drive through Cajun Country. Out there, far from New Orleans were wild iris, flying their purple flags, stubby nutria rooting in the swamp, and sluggish gators hunting for their first breakfast in a while. Later, in a small restaurant, a woman fed me crawdads off a beer tray, crawdads they had the cook prepare for me because I wanted to try their brand of Cajun food. Not in the guidebooks. So, I’ll not, even closer to the trip, be able to tell Dr. Gerst exactly where I’m headed. I may have to prepare for the broadest problems. That’s ok with me. Even after three vaccinations yesterday. Oh, yes. I’m going to Southeast Asia. So, Dr. Gerst hesitated, I blushed. Ummm. Well, you know I have to ask you about Hepatitis B. Blood borne. I’m not an IV drug user and I don’t visit prostitutes. Is there any other way I can get it? No. Well, a transfusion. But... Let’s skip it, then. More on preparations for the journey later.

"My advice to you is not to inquire why or whither, but just enjoy your ice cream while it's on your plate -- that's my philosophy. " - Thornton Wilder

In a piece I read yesterday on Thai and Cambodian sculpture, a point I had not understood about Buddhism became clear. The Buddha achieved nirvana. We know that. But the article went on to point out that nirvana is a state of existence incommensurable (great word, eh? Theirs. Not mine.) with the universe in which we live. Therefore, and here’s the punch line; what I’d not understood before: The Buddha is absent. Gone. Not here—literally. The three jewels of Buddhism stand in for the Buddha: Images of the Buddha, dharma, and the sangha. Thus, the three jewels are, in this plane of existence, the Buddha. In a more drawn out argument I won’t recapitulate here, the article goes on to contend the Buddha images are alive, and need care and treatment as living beings. As I read all this, the congruence between this study at the MIA and my impending trip keeps an exciting frisson going. After I finished that piece, I moved onto to a discussion of Angkor Vat and Angkor itself (Angkor the city was the capital of Cambodia for hundreds of years). The more I read the more excited I got about traveling there. So much that I’ve decided to streamline my trip a bit. I plan now to spend a week or so in Singapore, an equivalent amount of time in Bangkok, then a week on the trip to Phonm Penh and Angkor, followed by a week in Myanmar—Singapore, home. I made this change to slow the pace of the trip down a bit, to give myself a chance to sink back into the rythym of the cities and the sites of Angkor and Pagan (2,500 temples in Burma. Former city of a million people. Depopulated by the threat of the Mongol invasion in the 17th century.) Resistance to travel is new for me, though I’ve noticed it more than once in the last couple of years. In the past, “I like to go.” was my entire philosophy on travel. With nary a thought I’d pack up and head on out, these days, I notice some hesitancy. No more familiar bed. No more pillow with my scent on it. No dogs to greet me in the morning. No routine that helps my weight and exercise stay healthy. Plus all the hassles attendant with travel: airplanes, tickets, hotel reservations, schlepping luggage around. It feels as I write this like the “self-care fatigue” I described earlier. (I did describe this didn’t I?) If I didn’t, here’s the short version: I take meds, do aerobics, buy healthy foods, watch my food intake, get regular checkups, brush and floss, and now Kate and I have a Universal gym and a personal trainer (thanks to my Dad and the inheritance money). Oh, I sit with my good ear to company, practice defensive driving—anyhow, you get the picture. You do much of this yourself, I’m sure. I found myself a few months ago tired of it all. I didn’t want to floss anymore, take my meds, hit the treadmill. Blah. Blah. Humbug. Enough already. I’m too old and the habits too ingrained to really stop, but I wanted too. At least for awhile. Travel kicks up the ante on self-care to a high pitch. I didn’t use to mind, in fact, I used to find the extra work invigorating, especially since it meant no responsibilities for the domestic life. Now I find the domestic life nurturing so that incentive has dwindled, though it is still a relief to be away from home. Kate has never lacked packing and unpacking, moving on, but I’ve really enjoyed it. Lots of places to see, lots of things to do. I’ve paid the money, get as much in as possible. Not this trip. This trip I want to plan it so I can settle in, explore a few things at a leisurely pace. Sketch. Read. Sit through sunrise and sunset. Eat in lots of small restaurants. Meditate. This may sound obvious to you, but it’s a new way of contemplating travel for me.

Negative Space

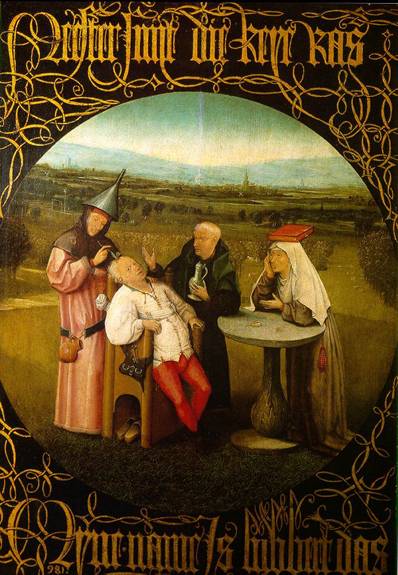

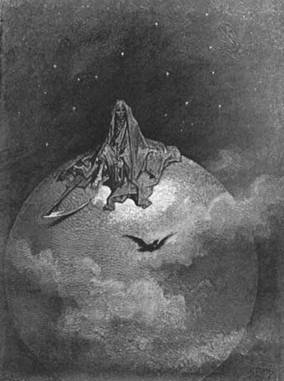

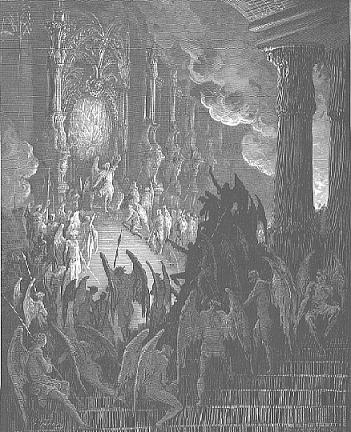

In a week my class on negative space moves into its own territory, it will become negative space itself as I continue to educate my brain and practice my hand and arm in the arts of representation. Over the last few weeks a flood of new information has poured in over the transom, at times threatening to inundate me. A point of congruence among the Jungian Seminar, the MIA classes on Southeast Asian Art, and Sheila Asato’s drawing classes is image. Jungians contend image is the primary language of dreams, perhaps of the mind (I don’t understand how words fit into this picture right now.); images are the primary content for art history though a torrent of words surrounds them;, and, image is the point of drawing. I begin to get overwhelmed when wrestling with a new concept, a major one, and image qualifies. “Negative space is everything you can’t name,” Sheila said this morning. What this means is, for example, what is the space between your lip and your nose? Among your fingers and toes? The interior space of a doorway? Between tree limbs, leaves, flowers. Sculptors talk about negative space all the time. When Michelangelo spoke about chipping away everything from a block of marble that wasn’t the sculpture he saw there, what he took away was negative space, previously in stone and visible only in his mind’s eye over against the image to be, for the time being still stone, like its negative space. A picture is worth 10,000 words. An image is worth 10,000 words. Does that mean a drawing is worth a week’s worth of writing? It takes about a week of 2,000-2,500 word days to produce 10,000 words. This is a koan, as far I’m concerned, and a good one. Even if it is worth 10,000 words, how many words is the negative space worth, which, after all, defines the image. This koan is about condensation, concentration, titration, not, if I understand it, meaning, but content. In other words the image is its own meaning. An image is content accessible to the mind, as is language. So image comes to us with syntax and grammar, feeling and content, already useful, already memorable (literally) without the screen of meaning words carry in their dance between denotation and connotation. An aha here. My early visits to the art museum at Ball State and my early infatuation with Ingmar Bergman (my black and white period) represent my own, literally unconscious, imagistic education at work. An educational work I continued in movie theatres, art museums, and books right down to the present. So, we have images spilling around us all the time, a cascade of images, pulsing rushing entering our minds, and we have few tools, those of us not visual artists, with which to understand them, let alone produce them ourselves.

Many of us in fact pride ourselves on our iconoclasm, literally, the breaking of images. Our post-Gutenberg culture has a deep suspicion of image. It is, perhaps, in this light, no wonder other countries worry about contamination by American movies. Also, perhaps no wonder pornography has such an incendiary reputation. Or, in the same vein, but from the opposite direction, that painters have a mystical place in high culture, their work a realm of mystery.

I wonder though now whether this deep suspicion, this near iconophobia in some cases, comes more from our ignorance about the language of images, their syntax and grammar, than it does from their content. Does the power of image to speak directly to our mind somehow frighten us in the same way as immersion in a foreign culture where we do not understand the words spoken around us? Images have two pathways. I learned about these two pathways, one to the visual cortex and one to the brain stem on a PBS show: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/mind. (This is the website.) It may be that the brain stem path—which alerts us to danger or possible prey—processes certain images as dangerous or viscerally attractive. Since we have no or limited inner resources for discerning safe images from highly charged ones—other than, say, revulsion, disgust, lust, aggression—we have come to rely on the most basic, primal responses to keep us safe, or in-bounds according to cultural norms. It occurs to me this may be a primary vehicle for the pilgrim. The pilgrim travels hoping for the numinous, the wonderful, the joyful, the delightful, the mysterium tremendum, and finds it more often far from home because images created by other cultures slip even more easily past our iconophobic guards and tickle the urgency buttons hard-wired into our autonomic nervous system. The jolt, the imagistic thrill, puts us in touch with our Self, not the constructed persona. The immediacy of the unexpected powerful image can take us out of our selves (really, our ego), or more aptly, can lure us away from our ego toward our Self. Well, we’ve wandered far enough down this rabbit-hole for this week. Following the Great Mammoth, somewhere on the ancient path, I say to you, Blessed be.

Charlie Buchman Ellis Top < Previous Next > |