|

Disclaimer: This unedited, rough draft material is a year-long project in response to our 2004 theme: pilgrimage. It is meant to be a dialogue between myself and my fellow Mammoths and any of you who happen along. It is intentionally not polished, nor is it finished. Charlie Buchman Ellis -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- An abbreviated week since I leave on Thursday for Denver, Colorado on a mission to pass on furniture to those who will, hopefully, create the grandchildren to whom they can pass it on and Kate and I can spoil. Yesterday I attended an all day Symposium on the Miller Collection, largely Roman portrait sculptures. I have predicted a classics renaissance for some time (if you predict something often enough and long enough, it may come to pass by exhaustion or happenstance. Tip of the Prophets trade.) and at this Symposium I found ample to reason to believe this renaissance may already be underway and ample reason to believe that, even if it is, it won’t take. Underway: there are a lot of folks still engaged in classical scholarship and they gather to discuss it once in a while. Spartacus the remake. Gladiator. All the interest in new translations of the Odyssey and Iliad, Dante’s Divine Comedy. Well, if I’m honest, I don’t see a lot of information to support my hypothesis, just wish fulfillment. I have, however, over the last few years made a conscious effort to read particular classics I had not read before and re-read one’s I had—this accounts for my hope that I’m not alone. Perhaps I’m a hopeless humanist, stuck in the days of broadly educated persons, generalists who seek the long lived threads in human life, in the fabric of the universe, and attempt to weave with them, a tapestry for our time, one neither wholly new, nor one based only on traditional design. If my pilgrimage is about one thing, it is about weaving such a tapestry, a cloth to hang on the wall of our inner sanctuary, a living picture. Still, I found in the Symposium ample reason to believe such a tapestry will interest only a few. Many will find the contemporary aspects intriguing, and I do too, but so few will sift patiently through the thoughts of Plato, Herodotus, Goethe, Ovid, Dante, Melville, Tolstoy, Blake, Yeats—even Rumi, Rilke, Stephens, Emerson. Even fewer seek out our rich global artistic heritage in painting, ceramics, sculpture, crafts, furniture, music. Ah. I feel elitist and Eurocentric as I write this, yet it is not what I want to convey. How can I say the joy, the peace, the delight, the perspective, the comfort, even consolation I find in the world’s imaginal realm. Do you feel it, too? Let me see. As I’ve grown older, passed the mid-point of life and entered on the labyrinth moving toward death, I find myself surprised at how much I enjoy the journey. I just learned last night that Pele’s Polynesian root word means to wander, to meander. Here is a good metaphor: Pele is the goddess of life’s final journey; she is the one who can guide our wandering toward the fiery essence. Pele is the goddess of the right hand spiral. She leads us to the gate guarded by Hecate, and can, like Virgil, guide us even past Hecate. What I am saying here? The language of the classics and of the world’s great objects, music, theatre can blend with our spiritual journey, our pilgrimage, blend and enrich, even provide a context in which the journey itself makes sense. Why? Because these classics—and I’m not limited to Western arts—let’s add in Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian, New Guinean, Polynesian, Oceania, Aboriginal, Native American, speak of the human animal stretched and prodded and challenged and blessed; the human animal inflected, as Joseph Campbell puts it, by culture and history, yet the same animal, with the same origin—a womb, and the same destiny, the grave—and a time in between during which we live, both to make sense of life, but more to sense life, to let the life force given to each one of us express itself in our particularity, our cultural idiosyncrasies, yet in so doing, reveal the universal in each of our particulars.

Something important about my journey wrapped up in the paragraphs above, but I couldn’t get it unstuck last night. This was the core of it: I’m a hopeless humanist, stuck in the days of broadly educated persons, generalists who seek the long lived threads in human life, in the fabric of the universe, and attempt to weave with them a tapestry for our time, one neither wholly new, nor one based only on traditional design. If my pilgrimage is about one thing, it is about weaving such a tapestry, a cloth to hang on the wall of our inner sanctuary, a living picture. I’ve known for some time I travel in at least triple company, as I’ve said before: monk, poet, and scholar. Never, before these paragraphs, have I had a true inkling of what their vocation is as a group, or, said another way, what my Self needs to accomplish in this incarnation, or transmigratory locale, or, even, in this one, authentic life I have. It’s interesting, but the notion of the authentic, existential life does not conflict with multiple incarnations, or the transmigration of souls, or, with the dreams of life beyond this one. No matter what happens next, say, reincarnation as a crosswalk sweeper in Calcutta, a lama in far off Sikihm, a lumberjack in a Monty Python film or the transmigration of your soul to a great Druidic oak or the form of a blue whale, or, even, landing in some level of Dante’s Paradiso, this life, right now, right here, requires your full attention, and the best you can do with what you’ve been given. Rule #6: Don’t take yourself too seriously. Hmmm. Every bone in my Teutonic body and every strand of my northern European DNA vibrates against this notion except at the juncture it has with humility. Yes, believing your own journey matters very much in the great sweep of cosmic development is hubris: even the Hitlers, Roosevelts, Khans, Sungs, Suryothais, Moghuls, and democrats and communists and socialists and monarchists and dictators and egalitarian leaders, even Jesus and the Buddha and Vishnu and Shiva and the great masters of the Dragon’s Gate Taoist sect pale before the transformations of matter into energy and back again. Well, I admit Shiva and Jesus and Vishnu, being gods of one kind or another may BE the transformations of matter into energy and back again, but even so that only makes them third rock from the sun metaphors, not the the transformation itself. Entropy, in a word, rules. Still, I want to speak a word for taking ourselves seriously. Once placed in the appropriately small niche we occupy, I still believe we have a responsibility to ourselves, our families, our friends, our species, our home, the Earth, and to our solar system, and the galaxy of which it is part. This may mean I’m doomed to a sour, gray version of life, but if so, so be it. The world needs you. It needs what you and only you have to offer it. This is, in one sense, an echo of my Reformed theological version of vocation—what you can do, only you can do, and God (the universe, the human race, your spouse and children—whatever—your Self) created you for the purpose of engaging the world as only you can. “Ministry,” Frederick Buechner said, “is the intersection between the world’s great need and my gifts.” He could have said, vocation. So, I think the real deal is this: don’t take yourself too seriously, take yourself as seriously as possible—now, find the transcendent function here. Perhaps, it just occurred to me, this is where clowns come in, comics, surrealists, dadaists, and, maybe, fantasy writers. Anyhow, having said all that, this dialectic has proved very, very difficult for me. On my path I have lurched, veered, driven off the road with vigor toward the slough of seriousity, grimness and political humorlessness; then, at other times, toward the swamp of drugs, sex, rock and roll, and aimless wandering. The latter has led to strange locales, exotic intellectual ports, odd friends. Back to weaving the tapestry. Art may be one transcendent function—a place where taking oneself seriously and not at the same time, serves a higher function: say, beauty, insight, contrast, paradox. Another might be self-disclosure, the honest exposure of your pilgrimage to the view of others. When we can share with others the joy and frailty of our path, then we take ourselves seriously—for, after all, my path is the only path I have, yet we also recognize the humor of our efforts, the unexpected in them, the prat falls we make in just muddling through. The Woollys. The Woollys might be a transcendent function, too. In the arms of other who care for us, our pilgrimage is taken seriously, yet we are known to each other. And the knownness, even if incomplete, allows us to see the other in their limitation as well as in their glory. So, I’m a tapestry weaver, yet, also a clown with a large red nose, downturned mouth, funny ears, and clumsy, oh so very clumsy big feet. Perhaps the two of me, and the three of me, somehow transcend to create a one of me. I have the trailer on the Tundra, clothes packed, itinerary laid out. I get excited when I’m ready to hit the road; the hours in the truck alone, listening to books or music or meditating, seeing America as it changes, subtly at first, then dramatically, different accents and changed landscapes. Cheeseheads and Viking horns give way to cowboy boots and Stetsons. On my first trip to Denver three years ago I realized the Rocky Mountain Front Range marks the boundary of my country. On the south I go as far as Oklahoma, then over into the deep south, up along the Mississippi adding in Kentucky, Indiana, Michigan and Ontario. This is, in every way, my home. I was born here, lived all my life in its confines, and have become a husband, father, and adult marked by its customs, language, its weather, and the land. It felt a bit strange to have this realization, because I think of myself as a citizen of the world, and, I am, yet, each citizen of the world has to have a locale of their own and mine is the center of the North American continent. I’ve read arguments that there are coastal folk, a so-called educated elite, who are, in effect, countryless; their loyalties more to global corporations, movements, organizations, and their lives lived in apartments, rootless and airborne. This may be so. I don’t know, but if it’s true I feel sorry for them, for to be from everywhere is to be from nowhere. Now I don’t think NASCAR races, brats and beer, Friday fish fries, basketball tourneys, farming, automobile manufacturing, cattle and hog raising, commodity trading, and the Kentucky Derby are high culture, but they are culture; the one I know in my gut, to whose rhythms I have come to know my own. A Memorial Day parade, Christmas decorations and snow for the holidays, white clapboard and large brick churches, a sense of solidity, of hereness occasioned by a central location on a large land mass, the extremes defined by direction: north-cold, south-hot, the plains where vast oceans of wheat yield to combines which ride its crests, the cities of the Great Lakes where commerce and steel and making things happen, the Great Lakes themselves and the vast bodies of fresh water in the Missouri, the Mississippi, Superior, Michigan, Huron, and the lakes of Minnesota. The convergence of the Big Woods from the east, the plains from the west, and the Boreal Woods from the north—huge deposits of iron ore, forests for timber, fish, and the soil, the fertile soil. Native peoples, adapted to the lakes, the plains, the forests of the south, the rivers and valleys. Immigrants in waves, moving east to west, with some stopping each time the frontier moved, but some going on, too. In fact, if we maintain a historical conscious, and a geological/geographical one, too, we come to know our pilgrimage here as one made possible by the dreams and pilgrim journeys of so many others. So many. The famine Irish. The Annishinabe. Swedes and Norwegians cramped by primogeniture. Germans unhappy with Bismarck’s totalitarian state. Lakota, Dakota, Hunkpapa, Nakota, Appsalooka, Cheyenne, Cherokee, and before them the Mississipian cultures like the mound builders at Cahokia and Anderson, Indiana and the Natchez nation who created the beautiful road through Mississippi and Tennessee. The vast numbers of the enslaved, first oppressed in the hot south, then, made mobile by emancipation, oppressed in the cold north. All these and many more, their ghosts and their dreams, the colors they loved, the architectural forms they cherished, the languages they spoke, the governmental forms they developed, the foods they ate, even the music and art they imagined into existence, all these form the road on which our pilgrimage happens. We are not alone, were never alone, cannot be alone; yet, paradoxically, we are, in fact, born alone and die alone. Which is more real? I love traveling this land, even though much of it I’ve seen many times, it feeds me in a way much different from my travels to foreign lands, where I move as stranger, as one visiting, a wayfarer. Here I travel as a person of the land, one among his own people, where the smells and foods and language and houses and even the hills, valleys, and waters are known; yes, they may all differ to some extent, but not to an unknown extent, rather within a range of comfort and familiarity. I travel here, not to know the other and through the other my self; here I travel to know myself and those who share my life. At one time, when I was younger, this thought might have felt constrictive, narrow, but now, as I grow older, I understand the need to have place, to feel at home—in a house, a town, a city, a state, a region, and, of course, a country, too, and a world and a universe, yes, but first, to belong. And it is here, in this vast space, I belong.

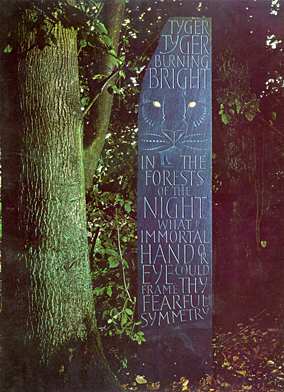

To finish I offer the three poems I chose from the New Oxford Book of English Verse. I selected these poems because they speak to me of the zeitgeist, either of our time, or of the time just past—the 20th century, the century of our birth, the millennia, too. In either case, for me, they spread wide upon the page and in the heart the sense of a time gone out of joint, not right in ways too hard to name: wars, rumors of wars, holocaust in Germany, Ruwanda, Russia. The death of god. Flu pandemic. Polio. Aids. Cholera. Malaria. The failure of communist revolutions in Russia and China. A gathering storm in our atmosphere, the warming and poisoning of the air, water, and earth. The rise of a mean spirit in the public arena. Terrorism. Racism. In the forests of the night what immortal hand or eye could frame thy fateful symmetry?

I know these are dark thoughts and they defy rule #6, yet, for me, clarity and truth demand voice. Blake, Arnold, and Yeats speak with an awful thunder, yet like an August thunderstorm, they may break the grasp of the over-heated time in which we live and bring a cool northerly season to a warring race. May it be so.

The Second ComingW. B. Yeats

Look for a trip to Denver and Points West summary sometime the weekend of May 1, Beltane. Until then, I am your friend, and proud of it. Charlie Buchman Ellis Top < Previous Next > |